Here's a small sample of our recently published research. You can find more studies by visiting the Google Scholar page for Dr. St. Peter, and find a link to our most recent publication here.

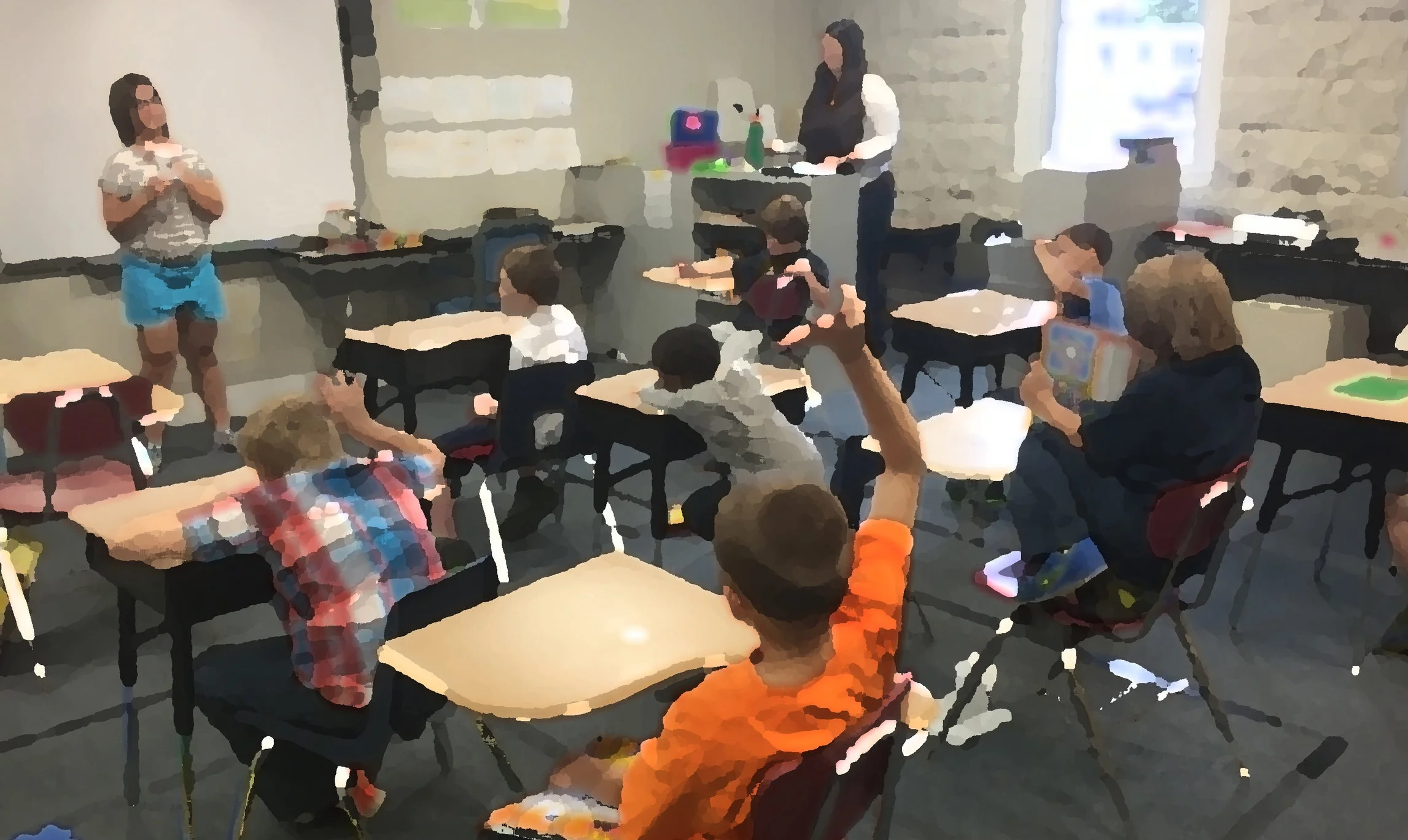

School-Based Research: “Free” rewards must be given consistently to effectively suppress Problematic Behavior in Schools

This study was Stephanie Jones’ Master thesis. Stephanie was working with elementary students with age-typical skills, but who were struggling with their behavior in the classroom. She first did an assessment that showed that problematic behavior was more likely when the students had to put away play items. As a way to reduce problematic behavior, she gave free access to play items. This was effective for all three students. She then looked at what happened when play items were sometimes restricted (or omitted, so an omission error) or when they followed problematic behavior in addition to being available freely (called a commission error). At least one type of error was problematic for each of the students. Stephanie’s findings are important because they suggest that teachers have to be very careful about the use of “free” rewards in the classroom.

Here is the technical abstract from the study:

Noncontingent reinforcement (NCR) is an effective behavioral intervention when implemented consistently. NCR may be particularly well-suited for use in schools because of its perceived ease of use. However, previous laboratory research suggests that NCR may not maintain therapeutic effects if implemented inconsistently. Inconsistent implementation (i.e., implementation with integrity errors) is likely when teachers are expected to implement NCR alongside many other responsibilities. The purpose of this experiment was to assess the efficacy of NCR with integrity errors for students with disruptive behavior in a school setting. We evaluated NCR with errors of commission (reinforcers contingent on challenging behavior) and errors of omission (omitted responseindependent

reinforcers). At least one error type was detrimental for each participant. These results, in conjunction with previous findings, suggest that NCR should be implemented with high integrity to remain consistently effective. Suggestions for the use of NCR in schools are provided.

Conceptual Evaluations: RETHINKING HOW WE ANALYZE PROCEDURAL FIDELITY

From Percentages to Precision: Rethinking How We Measure Treatment Fidelity

In behavior analysis, we often analyze procedural fidelity—how closely someone follows a treatment plan—using percentages. It’s simple: if a teacher implements 8 out of 10 steps correctly, that’s 80%. But does that number really tell the whole story? In our recent article, we explore the limitations of relying on percentages alone. They’re unitless, easily distorted by small changes, and can hide meaningful differences in performance. For example, two very different teaching sessions might both show 90% fidelity—even if the number and types of opportunities to implement varied widely.

We propose adding response rate—how often someone implements steps correctly or incorrectly per minute—as a more sensitive and informative measure. Rates help us see not just accuracy, but fluency. They reveal patterns that percentages miss, like steady improvement, increased errors under pressure, or variations across time. By combining percentages with response rates, we get a richer, more actionable picture of fidelity. This shift can improve training, feedback, and outcomes—especially in real-world settings like classrooms and clinics.

It’s time to move from “good enough” metrics to more precise tools that reflect the complexity of behavior.

Here is the technical abstract:

In some domains of behavior analysis, summarizing data as a percentage is nearly ubiquitous. This is certainly the case when behavior analysts report data about procedural fidelity (the extent to which procedures are implemented as designed); fidelity data were reported solely as percentage in 423 of 425 recent studies published in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. In this article, we critically examine the use of percentage, especially in the context of analyzing procedural-fidelity data. We demonstrate how exclusive reliance on percentage can obscure important nuances in fidelity data and how adding response rate as a metric offers a more precise understanding. To illustrate our points, we include reanalyzed data from a recent evaluation of procedural fidelity in public schools. We conclude with practical recommendations for adopting rate as a metric in the analysis of procedural-fidelity data, thereby building on contributions of notable behavior analysts like Henry Pennypacker, who prioritized continuous, dimensional approaches to measurement.

Staff-Training Research: Accuracy of Behavioral Data is affected by the features of the behavior

This research idea sprung up as a side project for doctoral student Marisela Aguilar. Marisela has a long-standing interest in procedural fidelity, having gotten a start on fidelity research as an undergraduate student. Like anything, measures of fidelity are only useful if the data collected are accurate. Marisela and Abbie (a doc student peer) determined how well undergraduate students collected fidelity data from videos. The videos showed mock therapy sessions, but the extent to which the therapist implemented the treatment protocol systematically varied. Participants found it more challenging to collect data when the therapists made more errors. This is important for people who are teaching people to collect fidelity data! Basing the training only on “good role models” (that is, sessions with high fidelity) might make you think that the person can collect data on any circumstance. In reality, including some lower-fidelity videos may be important to teach people the difference between correct and incorrect implementation and how to accuracy record it on a fidelity checklist.

Here is the technical abstract:

Monitoring the fidelity with which implementers implement behavioral procedures is important, but individuals tasked with monitoring fidelity may have received little training. As a result, their data may be affected by variations in implementers’ performance, such as the frequency of fidelity errors. To determine the extent to which the frequency of fidelity errors affected data accuracy, we used a multielement design in which novice observers collected fidelity data from video models with three levels of programmed fidelity (40%, 80%, and 100%) of a procedure based on differential reinforcement of other behavior (DRO). Participants collected fidelity data with lower accuracy, as indexed by interobserver agreement scores, when errors were more frequent. These findings suggest that individuals collecting fidelity data may need additional supports to detect and record all errors when procedural fidelity is low.

Collaborative Research: Linking Loopy Training to Behavior-Analytic Principles

It’s fun to connect your professional and personal life sometimes! I have ridden horses since I was a small child and sought out a trainer who was an expert in the use of positive reinforcement methods (purely for personal gain with my riding) named Alexandra Kurland. There were clear links between some of the strategies that she had developed over the course of her professional practice and the scientific literature in behavior analysis, but these links weren’t documented in the research literature. When the Journal for the Experimental Analysis of Behavior issued a call for manuscripts connecting behavior analysis and animal training, we jumped on the opportunity to co-author a manuscript! It was a delightful process of learning to “connect the dots” and think carefully about our language and connections to each other. We also had fun talking about the experience of co-authoring a paper on Alex’s podcast, Equiosity. You can find the link to the podcast here: https://www.equiosity.com/single-post/episode-197-dr-claire-st-peter-part-1-loopy-training-article-in-jeab.

Here is the technical abstract:

The communities of behavior analysts and animal trainers remain relatively disconnected, despite potentially beneficial links between behavioral principles and the practices of animal training. Describing existing links between research by behavior analysts and practices used by animal trainers may foster connections. In this paper, we describe an approach used by many clicker trainers, referred to as loopy training. Loopy training is a teaching process built around the concept of movement cycles. Interactions between the animal learner and the handler are refined into predictable, cyclical patterns that can be expanded into complex sequences. These sequences include cues, target responses, conditioned reinforcers, and consummatory responses. We link the foundations of loopy training to existing work in the experimental analysis of behavior, compare loopy training to other shaping approaches, and describe areas for future research. We conclude with a series of recommendations for further developing connections between behavior analysts and animal trainers, using loopy training as the foundation for our suggestions.

Human-Operant Research: Nominally Acceptable Integrity failures negatively affect differential reinforcement

The finding that differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA) is efficacious at 80% integrity when continuous reinforcement is programmed for alternative responding may have contributed to a perception that integrity at 80% or above is acceptable. However, research also suggests that other interventions (e.g., noncontingent reinforcement) may not remain effective at 80% integrity. The conditions under which 80% integrity is acceptable for common behavioral interventions remains unclear. Therefore, we conducted two human-operant studies to evaluate effects of 80% integrity for interventions with contingent or noncontingent intermittent reinforcement schedules. During Experiment 1, we compared noncontingent reinforcement (NCR) and DRA when implemented with 80% integrity. During Experiment 2, we compared 2 variations of DRA, which included either a ratio or interval schedule to reinforce alternative behavior. Results replicated previous research showing that DRA with a FR-1 schedule programmed for alternative responding resulted in consistent target response suppression, even when integrity was reduced to 80%. In contrast, neither NCR nor interval-based DRA were consistently effective when implemented at 80% integrity. These results demonstrate that 80% integrity is not a uniformly acceptable minimal level of integrity.